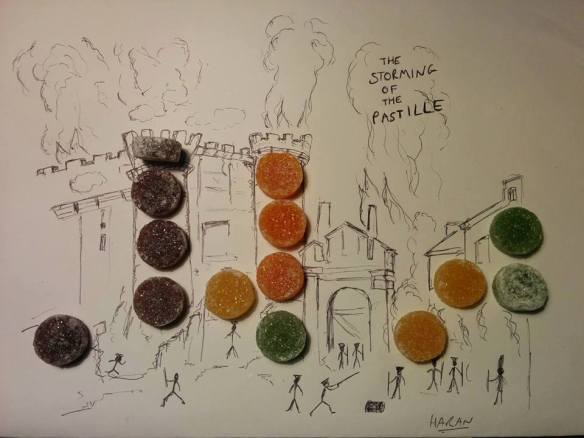

by Haran X

Dear Haran,

Thank you for your essay entitled, ‘The Top 10 Goals of Arsenal and England striker, Wellbeck.’

Unfortunately, we are unable to publish your article as we were actually looking for a lengthy, post-structuralist critique of the controversial French author, Houellebecq.

Yours regretfully

The Editor, London Review of Books

It would flout publishing etiquette and irrevocably destroy my self-respect to go back to the editor of LRB and resubmit a review of Michel Houellebecq’s sixth novel, Soumission. (That’s ‘Submission’ to people who can’t read French or make simple interlingual inferences). As a result, I’ve published my review here instead, on the Faking Lit website – a blog so popular it has an Alexa rank of 0.

The review

I ought to like Michel Houellebecq. As a lonely, misanthropic, sexually-frustrated adult male who blames my lack of mating success solely on the unbalanced free-market dynamics of the dating world, I really ought to like Michel Houellebecq.

In Whatever (Extension du domaine de la lutte), his first novel, Houellebecq advances the claim, that:

“In a totally liberal economic system certain people accumulate considerable fortunes; others stagnate in unemployment and misery. In a totally liberal sexual system certain people have a varied and exciting erotic life; others are reduced to masturbation and solitude.”

As a man who regularly finds himself crywanking after 1,472 right swipes on Tinder without a match, it’s hard for me to argue with that reasoning. Clearly I’m one of the liberal system’s losers, a veteran member of the sexually unemployed. And, unlike the economically unemployed, I don’t have friends with benefits.

In Atomised (also known as The Elementary Particles), one of the main protagonists is an undersexed, socially-awkward, academic type who uses terms like “interlingual inferences.” Jesus, what a pretentious, but nevertheless handsome twat.

Even closer to the bone, Daniel1 of Houellebecq’s fourth novel, The Possibility of an Island, is a sexually-frustrated, bald man who performs stand-up comedy. With characters like those, reading a Houellebecq novel is like reading a mirror. No, I don’t mean that the letters are back-to-front or that someone has drawn a cock and balls on them using condensation. Rather, I mean that Houellebecq’s characters so profoundly resonate with me. They’re lonely, bitter, serial onanists who pine for affection – the type of people ripe for radicalisation by ISIS, the alt-right or the gluten-free movement.

Given this affinity for his characters then, why do I have no love for the author revered by Random House as ‘the most important French novelist since Camus’?

In short, it’s because he’s boring. Samey. Dull. Samey. If the plots of all his novels were to be summarised into a single song lyric by the early 90’s rap group, Salt N Pepa, it would read:

“Let’s talk about my lack of sex, baby.”

Death by Snoo-Snoo

To be fair to Houellebecq; in addition to sex, he also talks about death; and arguably all great art is about sex and death. Tennyson’s Lady of Shallot, Sirizitky’s Emannuelle in Space and Motteux’s Autoerotic-asphyxiation Gone Wrong (Volume II) are all good examples of this. Crucially, however, Houellebecq’s novels are exclusively about lack of sex and death. And, for some reason, this combination of themes does not make for great art; instead it’s tedious, especially as a motif repeated across six novels.

To illustrate my point, allow me to supply you with the condensed storylines of Houellebecq’s first five novels.

- Whatever: man can’t get laid, later dies in car crash (possibly suicide).

- Atomised: man can’t get laid, later commits suicide.

- Platform: man can’t get laid, later commits suicide

- The Possibility of an Island: man who can’t get laid, commits suicide.

- The Map and the Territory: man gets laid sometimes (but only by paying for it), later dies alone.

(Warning: the preceding text contained spoilers).

In Submission, the sixth novel, Houellebecq changes his tune ever so slightly. Instead of dying, Francois, a man who can’t get laid, ends up converting to Islam. Finally! Vive la difference! But also, “plus ça change” – the book is still fundamentally about the same theme, namely a lack of sex and death. This is neatly embodied by the line:

“I didn’t even want to fuck her, or maybe I kind of wanted to fuck her but I also kind of wanted to die, I couldn’t really tell.”

There you have it, ladies and gentlemen, the best French author since Camus!

Even with Submission’s subtly different ending (i.e. Francois’ conversion to Islam), the fates of Houellebecq’s characters across his six novels now make for a rhyme that is far inferior to the one about King Henry VIII’s wives:

Died, died, died,

Died, died, converted to Islam.

French erection

Set in the year 2022, Submission takes place in a political climate where the National Front are set to win the French general election (or simply ‘general election’, as it’s known in France). Given the current state of French politics, this seems rather prescient of Houellebecq – Marine Le Pen could well become President.

Less realistic, however, are the socialist and centre-right parties joining forces with a new party called the Muslim Brotherhood. Still, Houellebecq’s prediction is vastly more accurate than a 2016 election poll or a 1987 Michael Fish weather forecast.

Anyhow, these various non-National-Front parties bandy behind the Muslim Brotherhood candidate, Mohammed Ben-Abbes. He gets through to the second round head-to-head run off, where his opponent is Marine Le Pen. Again, this scenario seems unrealistic for the year 2022, especially given the National Front’s views on climate change:

The National Front in 2012:

“I am not sure that human activity is the principal origin of this phenomenon”

– Marine Le Pen

In 2022:

*gurgling noises*

– Submarine Le Pen

Somewhat predictably (from a literary point of view), Mohammed Ben-Abbes wins the final and now, shock horror, France has its first Muslim President. (It is unclear as to whether or not he is the son of a bus driver).

Meanwhile, fearing that he will no longer be able eat his favourite dish of alcohol-cured bacon, Francois, a 44-year-old academic at Paris-Sorbonne University, decides to quit his post and leave town. Presumably out of a modern hipster desire to brew craft Trappist beer, he takes refuge in a monastery in a far away French town.

Like every other Houellebecqian character, Francois is a self-pitying, lonely male who constantly bemoans his lack of sex and evaluates women solely on their aptitude for fellatio. It later transpires that Francois’ hot, young, Jewish girlfriend, named Myriam, has also decided to quit town. Wary of the new the Muslim government, anxious about rising anti-Semitism or perhaps motivated by a need to always outdo her boyfriend, she departs to a place that is even further away, Israel.

Understandably, Myriam’s departure upsets Francois; within him swells a sense of loss. Yet to Francois, this isn’t about a looming loss of companionship, emotional warmth or basic human attachment. No, instead he’s sad at the thought of all those blowjobs he’s going to miss out on. To Francois, Myriam is basically a Jewish Henry Hoover with a wig. In fact, the reader is baffled as to how François hasn’t already fallen in love with a Fleshlight or a hole-in-the-wall. After all, as he opines,

“For men, love is nothing more than gratitude for the gift of pleasure.”

Muslamic Ray Guns

When he’s not talking about blowjobs and DVDA, Francois waxes lyrical about the life of Joris-Karl Huysmans, the French novelist upon whom he wrote his PhD thesis. Like many academics who try to justify their Arts and Humanities Research Council funding, François makes the mistake of thinking that anyone beside himself cares or stands to benefit from his research. What follows are dull, protracted paragraphs about the colour of Huysmans’ skirting boards and other obscure “research” findings that are somehow supposed to advance civilisation. Arguably, Houellebecq is deliberately parodying the liberal intelligentsia here: those who cannot create art themselves are condemned to practise only lengthy critical (over) analysis of other people’s work. Sometimes on blogs.

Fortunately, Francois manages to bore himself (as well as the reader) with all this talk of Huysmans; he soon leaves the monastery and returns to Paris. Of course, Paris has now changed. It’s become Islamified. Women on campus are adorned with hijabs, Disneyland Paris has become a giant mosque; cafes spice up their Halal sushi with a dollop of Wahhabi.

Mohammed Ben-Abbes (the Muslim President, whose mother was Uncle Ben’s sister) has also expanded the EU and acceded Algeria and Saudi Arabia. This may sound preposterous, but bear in mind that Australia have entered the Eurovision Song Contest since 2015.

Francois’ previous workplace, the Paris-Sorbonne University, has changed too – it’s now been renamed the Islamic University of Paris-Sorbonne. Congruent with this, the university’s employees have also muslamified themselves. One recent convert to Islam, professor Robert Rediger, boasts to Francois about his multiple wives like a syphilitic bore at a stag-do. Naturally, this piques Francois’ interest. To him, the equation is simple: multiple wives = multiple blowjobs. Rather than marry a Hydra or buy several Henry Hoovers, Francois increases his fellatio opportunities by cannily converting Islam; he submits to the will of Allah.

So, is this book a satirical dig at Islam? Or is it a criticism of left-wing academics, whose reticence and anxiety over being seen as Islamophobic has led to destruction of Western secularism?

At the end of the book, it finally dawns upon the reader that ‘Islam’ means ‘submission’; and ‘submission’ is an integral component of BDSM. So, no, Houellebecq’s Soumission isn’t an edgy socio-political or religious satire, comparable to Orwell’s 1984 or Rushdie’s Satanic Verses. No, far more dully, it’s about sex, baby.